We interviewed Cristian about his journey to success. It’s a story of limitless curiosity, persistence, and the importance that mentorship plays in reaching your dreams.

Look up!

I grew up on the south side of Stockton, the second son of Mexican parentage. My dad was born in Stockton, 1st generation, Mexican American. He builds houses. He literally can build a whole house. He’s self-taught, never went to school or college, just started off as a laborer and learned over the years. He had a great mentor who got him on the right track. My mom was born in Purépero, Michoacán, Mexico. She worked as an admin. She’s also a self-taught accountant. My

parents are both intelligent, hard-working, self-motivated, practical people. My parents had big dreams for their children. They sent us to a private Catholic school. We lived in a rough area and the public schools were terribly underfunded. My parents knew that private schools were expensive but they found a way to make it work because they didn’t want my brother and I to live the life they were living. They didn’t want us to struggle. They understood the importance of education and told us you need to do well in school because you do not want to be what you see around you.

My dad got me my first telescope when I was about eight or nine. I remember trying to use it one night with my brother, who was five years older. We were unsuccessfully trying to look at the moon. I think it was one of those automated telescopes where you use coordinates. It fell over, slammed on the ground, and got dented. Disappointed, we packed it away.

My mom and I liked to go to Barnes and Noble and browse the books. She bought me this giant encyclopedia, a coffee table book called The Universe. I would look at it all the time and just be like – wow, this is incredible. From then on I really wanted to be an astronaut.

Years later when I was in high school, I remembered that telescope and decided to see if I could work it. I set it up in the backyard and took a look at Saturn. At that moment, I was just like “I’m still fascinated by space–and this is exactly what I want to do, something related to space.”

Mentors and Role Models

One of my big role models growing up was an engineer named José Hernández. He’s the first Mexican American astronaut. He’s also from Stockton. His parents were migrant workers. He went to the University of the Pacific where he studied electrical engineering. I was very lucky to meet him one day at a fundraising event for this group called LULAC (League of United Latin American Citizens). That was my first exposure to learning what engineers do. From then on, I was sure I wanted to be an astronaut and follow in José’s footsteps. After getting his masters degree in electrical science, José went on to work at The Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. He literally broke down racial barriers to becoming an astronaut! I mean this guy, he learned how to fly a plane and he learned Russian. José basically found out what all of these NASA astronauts have in common. He figured out ‘how do I get there’ and he did it!

I applied that same kind of logic to my own life, knowing I wanted to be a mechanical engineer or a NASA mission specialist engineer like José. I wanted to go to the University of Southern California and study aerospace engineering, but I didn’t get in. I ended up at the University of the Pacific in my hometown–the same university that José had studied at. My mom worked there, so I got my tuition greatly reduced, making a really good college more affordable.

Engineering isn’t an easy subject. I remember my first two to three years, I did not like mechanical engineering much. It was a lot, and I had to learn how to get through it. I registered for an elective in optics offered by the physics department. This is where my career exponentially took off. I met professor Dr. Elisa Toloba–both her and her husband are astronomers from Spain. She showed us giant telescopes in class. This immediately tugged at my inner child. I had been totally captivated with the images from The Hubble Space Telescope. Until this point at 20 years old, I didn’t realize ground-based telescopes like Keck and Lick Observatory were doing stuff. I knew there were giant observatories but I had no idea where they were or what they did. Dr. Toloba opened my eyes to a new field. I was asking questions in class, like “who builds these telescopes? Are you telling me the astronomers do; ’cause I don’t really see that kind of curriculum being taught–at least in the physics department.” “Actually you do, the engineers. There’s literally a whole team of engineers who are working on building these telescopes. Astronomers are telling the engineers this is what we want to build and the engineer builds it for them, or maybe goes back and tells them that’s not possible,” she said. Dr. Toloba could see how interested I was and reached out to UCO’s recent interim director of University of California Observatories, Connie Rockosi, on my behalf to ask what route I should take to work on instrumentation.

Dr. Rockosi is currently leading instrument efforts at UCSC, she kindly sent a really insightful email back to my professor saying – “If he wants to do instrumentation building, then he doesn’t necessarily need to get a graduate degree, but he should get as much lab work as he can. Pursuing a master’s degree would expose him to research and hands-on lab work, the kind of stuff that you would need to work at the University of California Observatories Lab.”

From this moment on I wanted to build the biggest telescope in the whole world!

This felt like a big giant mountain to climb. I didn’t know how I would get there, but I was determined I would. I finished off my undergrad and started looking for graduate schools. I knew that I needed to be a standout student to have any chance of success.

I’m thinking, where should I go to get that possibility of lab experience? In southern California you have The Jet Propulsion Laboratory and you have Carnegie Observatories. I didn’t have the opportunity to get a bunch of scholarships, so I looked at the state schools. The best state school in engineering in that area was Cal Poly, Pomona, so that was my number one choice. My cumulative GPA was below 3.0 at this point, but in my last two years of undergrad, I made sure I had

an above 3.0 GPA every semester until I graduated. I never got discouraged that maybe I had messed up before. I just figured, if this is what I need to do, I will do it. So my last two years of undergrad I took 18 units a semester, which is basically a full course load and then some. I picked up a physics minor too. I studied cosmology and astrophysics and took a modern physics class. Basically, everything that a physicist would take minus all the math! I took all those courses and surrounded myself with the kind of work I wanted.

My mom’s Mother’s Day present in May 2019 was seeing my brother and I graduate from college. We’re the first to graduate from college in our family.

A gap year – The importance of experiential learning

I wanted to work on getting exposure to as much as I could in order to make myself a more attractive candidate for the future. Taking a gap year provided me with that opportunity. I volunteered at the physics department of The University of the Pacific, asking to work on projects for more experience. I got to work on a 3-meter radio telescope dish. I helped with assembling the dish and testing it with two other students who were doing their senior projects on the radio telescope dish. I also had a go at getting into coding with Python as I knew that astronomers and astrophysicists use Python and Jupyter Notebook.

Graduate School – An important step to professional success

I remember feeling like a burden in a way. Like gosh, I’m studying and studying. I’m not getting a job. I want to do all these things that I don’t really know anything about. My parents were, as ever, super supportive. They reminded me — we want you to be happy and successful, follow your dreams. Don’t stop. If you need to go to graduate school, we’ll help you with graduate school.

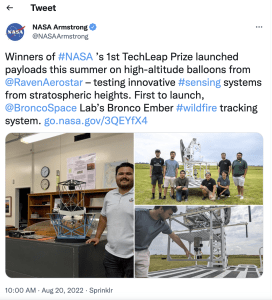

I applied to graduate school and then the pandemic happened. Everything was up in the air and uncertain. On the plus side, I got into Cal Poly! My first year, I was enrolled full-time as a graduate student, studying remotely at home. I wanted to finish in two years and I wanted to have a very open second year so I could work on any projects or thesis. I heard about this club on campus called Bronco Space, they made these tiny satellites called CubeSats–effectively a miniature of a very large satellite, as it has all the same components. There were 15 students in the club and I was the only grad student, I ended up leading the team. We developed a design idea and things were going really well. Michael Phamm, who is the club director, found out about this NASA TechLeap Prize. NASA had just released a solicitation for people to submit their design ideas to build an Earth CubeSat observing platform to look at what could be seen from up in the atmosphere. The idea was you could make a design, prove it works on Earth and then send it to study the moon for example.

Networking is everything

Dr. Toloba put me forward for a weeklong summer school program at Berkeley called Astrotech, run by (ISEE – Institute for Scientist & Engineer Educators). They bring together graduate and undergraduate students from all over the country. It’s a great program that exposes you to the latest astronomical instrumentation in the field. Thanks to the program, I learned about detectors and how they work. This fed into the NASA project with the Bronco Club. It gave me ideas about how we could use our team project to detect fire and what kind of sensor or camera would work.

After Astrotech, I went back to Cal Poly and told the project team about how we could use our observing platform to detect fire. The sensor would be low cost as it doesn’t need to be cooled, it doesn’t need any special expensive metals. I wouldn’t have known any of this if I hadn’t gone to Astrotech. I also met Dr. Renate Kupke at Astrotech. She was one of the instructors on the topic of optics and optical design. That was a very opportune meeting as I would later appreciate. Meeting and networking with all the people at AstroTech took our NASA proposal and my knowledge base to another level. The proposal was sent. It was now a waiting game.

Stepping up! – The Bronco Ember Platform

Six or so weeks later, I got a call. Our proposal to NASA had been awarded $200,000 for production. We were blown away. We had only requested $80,000! NASA said, “We’ll arrange for you to meet the NASA team. You’re going to build your project.”

I had no experience doing anything like this before! I leaned into my whole philosophy of “I don’t really know what I’m doing – but I know I can get there.

That first NASA meeting was in October 2021. I was having a borderline anxiety attack just talking to these people from NASA. They were crucifying our project. Questions were flying at us: “Well, what about this? What about that? We’re being hard on you, but just realize it’s because we want you to succeed. We want you guys to send this satellite up. That’s why we’re giving you money–we believe in you.”

The whole last year of graduate school I was working 16 hour days. My classes were exponentially harder than any undergraduate course I’d done. Simultaneously, I was working on the NASA project.

We had a design review in February 2022. NASA approved what we’d done. We had another design review in May. They loved it.

3… 2… 1… Liftoff

The flight that took our high altitude balloon up was on July 8th from Sioux Falls, South Dakota. It reached near-space. We got pictures back and were able to look at the ground. Although our test fires were not detected on this flight, the system test provided validity to the technology concept.Further calibration of sensors and software is planned for continued development of the Bronco Ember platform.

https://www.nasa.gov/feature/winners-of-first-nasa-techleap-challenge-take-flight

NASA plans to put our satellite on another flight next summer. This time we’ll be on a long-term flight. Our satellite will be up there for several days. That way we’ll know whether or not our detection system works as we’ll have more opportunities to observe the test fire sites. The Cal Poly Bronco team will be running the next test. I’ll be a consultant.

The goal is in sight!

Through a Slack channel that had been created for the participants of AstroTech 2021, I saw that Dr. Reni Kupke had posted a job at UC Observatories, for a Research and Development Mechanical Engineer position. I asked Reni, an optical designer at UCSC, if it was worth me applying as I wouldn’t be finished with school until possibly June of the following year. She told me that for the right person they would wait. Encouraged by Reni, I applied. I got an interview in January 2022! The following month they asked me to come up for a site visit. I walked the whole place, and met everybody. It was really inspiring. I really, really wanted the job.

In March I was told I’d got the job!

Working on exciting next generation projects!

Currently I’m 100% on SCALES which has been a huge learning experience. I’m part of a big team working in many locations here in the US and the sub-continent on different parts of the SCALES instrument. I learned that working on SCALES means you have a bunch of stakeholders and a bunch of customers. You’re making the end product for the scientists to do their work. It’s amazing to be part of such an important project and one that is so collaborative.

Deno Stelter is the SCALES instrument scientist, he gave me an entire walkthrough of the project when I started. If I have questions about how the piece I’m building relates to the rest of the SCALES instrument, I talk with him.

My project manager is Nick McDonald, a mechanical engineer at UCSC. He works remotely from his home in Washington. We meet weekly on Zoom to check on my progress. He gives me a lot of support. There are other very experienced engineers working around me. The staff at UCO Technical Labs are a fountain of knowledge. I can go to them for general engineering questions.

Dr. Reni Kupke and Daren Dillion are working on the actual optics and alignment of those optics so I have to talk with them to understand what is required from my design.

The specifics and process of engineering my design piece

I am working on the forward optics (mirrors), specifically the static mounts. They don’t move, they just sit where they are. The way these mirrors are oriented is minutely important. When anything around them moves, it can not affect the mirror in any way. All the pieces of the final instrument have to meld together into a holistic design so when everything is put together it works seamlessly. I was running into a mechanical issue with my design, when we put a pin made of a different material on the back of the aluminum mirror. We had to consider what happens to it when it gets really really, really cold, as that causes materials to shrink a lot. The mirrors are made out of aluminum. To attach the mirror and fix it

in place, you need the strength of a steel pin on the back to hold it up, but steel doesn’t shrink as much as the aluminum will, so when it shrinks it starts to compress onto it. That compression isn’t really a lot, it’s just nanometers, but less than a hair width of deformation on the mirror surface causes image distortion. It’s essential that what I design eliminates the possibility of any unwanted movement so that the light that hits the mirror is perfectly received within tolerance. The solution is to mill out a circle around the pin, almost like a moat that takes care of the compression and results in stresses caused by extreme cold to be eliminated.

The work is exciting and rewarding. Exactly what I’ve been reaching towards for so long. I said I wanted to build the biggest, giant telescope in the whole world! SCALES isn’t a telescope but it is a ginormous instrument. I’ve been here for just four months, this place just feels like I’m home, a dream come true.

Pathways for future engineers

If you’re a high school student and want to go into this field–any field really–I would look at what kind of jobs there are. General engineering is just that, it could be electrical, computer science related, software engineers and that kind of digital engineering is obviously in everything. In the future there will be a big need for computer science and software engineers.

Think about who works on these things you are interested in right now. Where do they work? If you’re interested in the James Webb Space Telescope for example, that was made in large part by Northrop Grumman. What would you need to get to work there, or get an internship there? Northrop Grumman’s in El Segundo, Southern California. Companies tend to hire locally, so let’s say you don’t go to Stanford, Harvard, USC or UCLA, and you’re like me who went to Cal Poly, Pomona. There are a lot of students who go from Cal Poly, Pomona, to Northrop Grumman. So find a school that you know will get your foot in the door, a school that has collaborations with these companies. Do your research and work with those you know with experience in your field of interest.

The exciting thing to bear in mind is you might end up working towards a future dream job, but end up using the skills you’ve acquired along the way to work in a field that is similar but isn’t what you thought you were going to do. Or perhaps it’s a newly, as yet undiscovered, closely-related field.

My biggest recommendation is to network, network, NETWORK. Reaching out to those who work in the field that interests you with the sole purpose of asking how they got to where they are now provides priceless insight. Do not be shy in the pursuit of your dreams, but brave in chasing them. Be grateful to those who have helped you along the way and take every opportunity presented to you. There is no such thing as failure. Every experience is merely an opportunity to learn and further develop yourself as a professional and as a human being.

It’s not easy being disadvantaged from the start

Kids who look like me can get forgotten. The public school system can only do so much. When I was in 7th grade, one of my cousins was in 4th grade at a public school. She told me she was too dumb to go to college. I told her, “You’re not. Who says you’re too dumb? You’re not dumb. You’re gonna go to college.” Years later she told my mom, that conversation had stuck with her and she did go to college.

A big part of the success I’ve had is due to the love my parents showed my brother and I. It is very much the reason why we are where we are today and not in jail or doing something that we shouldn’t be doing.

Kids need a good mentor, they literally need someone to tell them, “Whatever is going on in your life, you’re gonna get through it. You got dreams–just literally aim for the stars ’cause you’re gonna make it.” You may come from a background that almost breeds failure and disillusionment, but it can also breed that desire for something better. Anywhere up is going to be better than staying there.

A couple of weeks ago I talked to my mom about chasing dreams. “Both your Dad and I wanted you to follow your dreams because that’s exactly what we wanted for you,” she told me.

I want to give a big shout out to my mom. She’s the one that has gotten me to where I am today. And a shout out to my dad, without his sacrifice, love, and example, I would not have the work ethic and resilience I have today.

I know that the next instrument I get to build will be unique just like SCALES is. I’m going to keep learning and building skills, picking apart problems, and following my dreams. I might get to be an astronaut someday. Watch this space.